Articles of Interest is a bi-monthly post on the five or so most interesting things I’ve read during the titular two-month period. The intent is for there to be a few weeks of “lag” time between when I first read the articles and when I curate this collection, so that my selection isn’t biased by ongoing hype or sensationalism. The articles aren’t necessarily published during this period, although many of them are – I choose my collection from what I’ve bookmarked over the two months. Here are my picks for February and March:

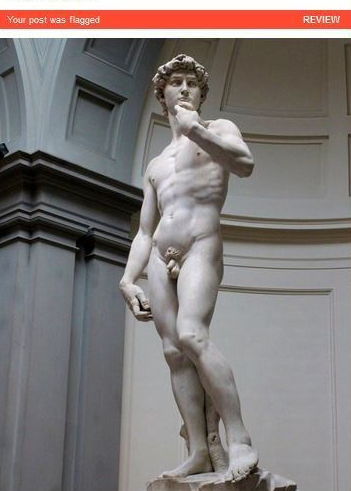

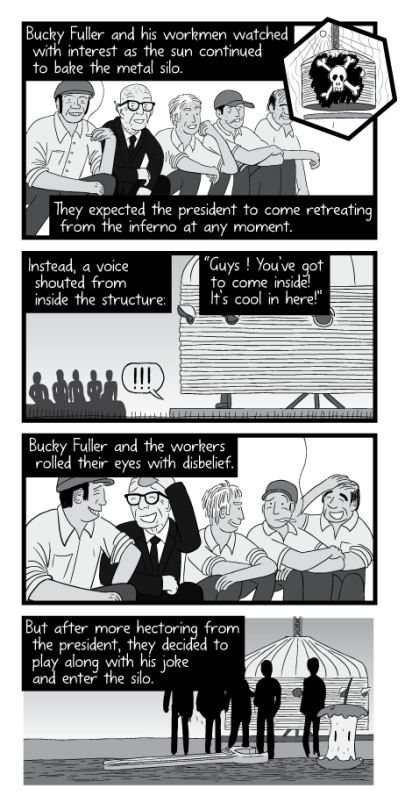

Buckminster Fuller’s Chilling Domes (with further commentary and notes here) by Stuart McMillen

I discovered Stuart McMillen during this interval of time, and summarily binged through his modest and very high quality archive of comics. I don’t endorse all opinions that McMillen espouses in his comics, but I do think that they’re all good and thoughtful reads. Two of them were in fact readings for the salon sessions I hosted last term: Supernormal Stimuli and Deviance in the Dark.

But I’m choosing to feature Chilling Domes, because while I enjoy culture war hot takes, they’re a pretty common sight in my corner of the internet. Conversely, it’s an incredibly rare delight when my interests in radical planning initiatives and quirky mid-century polymaths get indulged, at the same time. And an even rarer delight when that happens without the polymath getting real authoritarian or racist.

Check out the notes too for more on the physics and some plausible sounding explanations for why this phenomenon hasn’t been further explored in the almost-century since.

A Surgically Sculpted Face, the Newest Back-to-School Necessity by Wang Lianzhang

Chen isn’t worried she might not like her face after 10 years. “I can do more surgeries to change it again,” she says. “Any woman who can make the cruel decision to be pretty is brave. They will have better chances to make money and they will have a stronger desire to make money. They will be more hardworking than anyone else — because that’s the only way to cover the cost of further plastic surgeries.”

If you only had time to read one piece out of the five, make it this one. It’s such an interesting, meaty piece. And it’s talking about a social phenomenon that I guarantee you will make its way across the pond in the coming decades. It touches on so many interesting things! The role of social media in making being pretty more important than ever! The changing perception of what plastic surgery is (empowering, practical, incremental, something you can take out a loan for because banks recognize it as a good investment to boost your earning power)!! The very existence of FACE TRENDS!!! Can you imagine having to get a new face every five years to be considered stylish??? Holy CRAP.

I will say that this piece made me realize that maybe I’m not as transhumanist as I thought I was. I felt vaguely unsettled by the way that the interviewees spoke negatively about their original features. I thought the “before” picture of Chen Siqi was quite cute and I felt sad that she didn’t, or that her culture didn’t, and that in either case she felt better after having it changed. But since I feel comfortable with my own features, I’m definitely not in a position to judge, either.

And there’s some really interesting sociological aspects to transhumanism to think about here. If people want to augment their bodies with improvements that aren’t actually improvements but just because of societal norms or trends, would allowing that be a net positive for society? What are the circumstances under which it wouldn’t be? The closest frame of reference that I have is the Discourse surrounding facial feminization surgery for trans people, where body dysmorphia is seen as a reasonable justification for surgery. It looks like in plastic surgery circles though, dysmorphia in general is a big no-no. From this piece:

A small percentage of patients have body dysmorphic disorder and will never be satisfied with their appearance… it is essential for hospitals to hire psychological counselors to evaluate the patients.

There’s also this recent piece on incels getting plastic surgery (which JSYK I’m breaking my no-hype policy to post; this week it’s been linked everywhere and I’m extra grumpy about it because to add insult to injury it’s kind of bad and irresponsible as a piece of journalism), which had something similar to say:

Some surgeons will not operate on patients they believe may have body dysmorphia. “To me, that’s a red flag when someone has 200 pictures of themselves on their phone,” says Joe Niamtu, a cosmetic surgeon in Virginia, who declines to operate on many young male patients seeking sculpted faces. “The risk is they’ll never be happy.”

That’s going to be an interesting tension to observe.

And lastly, here is a hot take: when our generation reaches boomer-age, one thing our grandkids will post in the 2070 equivalent of r/forwardsfromgrandma would be memes about how much we suck because of our regressive af views on cosmetic surgery. We’ll be writing very embarrassing opinion pieces about how our kids are super selfish for choosing to not look like us at all, and it’ll get as soundly mocked as this piece is now. And they would be entirely correct for mocking us.

Why America’s New Apartment Buildings All Look the Same by Justin Fox

A TL;DR: In the mid-90s someone discovered that building codes classified wood treated with fire retardant as noncombustible, and because “stick construction” brings down the development cost of housing by 30% it’s quietly overtaken the States and Canada as well as a handful of other wealthy nations since then. It would depend on developers working against their own economic interests to close this loophole, and in the meantime there’s been quite a few sketchy fires and close calls. Some municipalities and industry professionals are starting to raise alarm bells about this issue.

Glenn Corbett, a former firefighter who teaches fire science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York, took me on a tour of some of New Jersey’s “toothpick towers,” as he calls them, pointing out places that fire engines can’t reach and things that could go wrong as the buildings age. “You’re reintroducing these conflagration hazards to urban environments,” he says. “We’re intentionally putting problems in every community in the country, problems that generations of firefighters that haven’t even been born yet are going to have to deal with.”

So that’s interesting and terrifying. But not really interesting and terrifying enough to be top 5 out of the hundred or so things I’ve read in this 2 month period by itself. It’s here because it made me reflect upon the planning education that I’ve gotten in the last four years, in a university that’s known to be the most STEM-oriented in the country. A planning education where I’ve taken seven or eight social justice-oriented courses, three being mandatory. A planning education where I’ve heard the term “stick construction” exactly once.

SlateStarCodex published a photo essay on the 2019 APA Annual Meeting, and his third thing is a similar observation about the psychology field. Like psychology, planning is a field where you do need a considerable amount of Wokeness to do your job properly. But should I have been learning more about building codes?

The Route of a Text Message by Scott B. Weingart

My leg involuntarily twitches with vibration—was it my phone, or just a phantom feeling?—and a quick inspection reveals a blinking blue notification. “I love you”, my wife texted me. I walk downstairs to wish her goodnight, because I know the difference between the message and the message, you know?

It’s a bit like encryption, or maybe steganography: anyone can see the text, but only I can decode the hidden data.

My translation, if we’re being honest, is just one extra link in a remarkably long chain of data events, all to send a message (“come downstairs and say goodnight”) in under five seconds across about 40 feet.

This is just such a neat piece of longform writing. I don’t know what else I can really say about it, I just really enjoy pieces that is a person enthusiastically infodumping about a thing that I know just enough about so that it barely doesn’t goes over my head. So that it barely punches me in the face, I guess? What makes this piece particularly appealing is the romanticization of tech that is a constant thread throughout. Not in the “it’s going to save us all” type of way which is boring and dangerous, but in the “look at this thing that we built, that generations of humans had a hand in shaping, that now exists in the world and against all odds works for us despite how much of it is cruft and duct tape” type way, which is MY JAM.

Fantasy Birding is Real, and it’s Spectacular by Ryan F. Mandelbaum

“Fantasy birding is basically the offspring of three unrelated obsessions of mine,” says Matt Smith, fantasy birding’s creator. “One is obviously birding, which I fell into pretty hard as a kid in Mississippi. The second is sports, baseball in particular, which always turned me on because of all the numbers. And the third is making things for the web.”

I just. Really love weird internet communities. They’re like online equivalents of stores that sell just one thing, which is another thing that I love.

And if you’re not familiar with 21st century birding, you might be surprised by the pretty impressive amount of online infrastructure and citizen-science-stry that happens when it comes to birds, which makes fantasy birding possible. I remember learning about the Cornell Lab and eBird in my second year field ecology course, and being blown away. I kind of thought that birding was a thing that retirees did with guidebooks from the seventies and a trusty set of binoculars? But reality in this case was so much cooler. And sometimes, you just need a reminder that reality is pretty cool, you know?