[epistemic status: actually pretty confident this time]

It was on a sewing blog that I first encountered the concept. Dozens of crisp white dishtowels all lined up along a kitchen back-splash on hooks; enough to be used indiscriminately, replacing the need for paper towels. I can’t find the original post, but it looked and read something like this:

It was an intriguing concept! I did feel guilty every time I used a paper towel for something that I technically could use a dish towel for, but we simply don’t have enough of them lying around. If we stock up, we can fit a small laundry basket under the sink, and every week or two we can run the dirty towels in a bleach cycle, keeping them clean and looking like new. We’ll never have to buy paper towels ever again, and the upfront cost would be tiny – hooks are 5/$1 at Miniso, and as I’m writing this, Amazon has 12-packs of dish towels for $19 – enough to make 72 towels, according to 104 homestead dot com.

Surely it’s a greener, more environmentally friendly alternative to paper towels! But alas, if I learned anything over my 3 years in the faculty of environment, it’s that reducing environmental impact is one terribly wicked problem. Now this is a long post even for me, so I’m sticking all the content under a readmore.

(Pressed for time? Hover here for the reveal)

1. A Very Necessary Preamble

One of the first essays that I wrote in my uni career was for an introductory environmental studies course, which was supposed to be about the effectiveness of a policy of our choosing to reduce environmental harm.

Something simple, to ease us into university level essay writing. I chose to write about the plastic bag tax, which I thought would be the most straightforward thing ever. (As a giant nerd, I feel obligated to mention here that I’m usually pretty ambitious about my essay topic choices, but on this occasion I was recovering from an eye injury that made it painful to look at screens for too long.)

I found that plastic bags are made from petroleum products which take millennia to break down, that plastic film is one of the least valuable recyclables, that they harm animals and oceans, and making one bag requires 4.8 megajoules (“enough for a car to travel 100 meters!”) and so on and so forth, and I thought, oh yeah this is easy, a plastic bag tax is the most obvious thing ever. One might even think that I got this essay in the bag.

But then I started researching the drawbacks, and that’s when things got a lot more complicated. Paper bags are, surprisingly, more awful for the environment – requiring almost 4 times as much total energy and 20 times as much water per bag during production and being somehow harder than plastic bags to recycle. Those “recycled” tote bags need to be reused 130 times before it “breaks even” on environmental impact compared to plastic bags – more if you wash them, which you should, if you don’t want e-coli.

And consider: what happens when you run out of plastic bags, and then you need to line a bin, or bring something leaky somewhere, or pick up dog poop? If your answer is to buy more plastic bags, doesn’t that defeat the point entirely?

When a problem is more visible, people consider it to be a bigger deal. Could it be possible that I only felt guilty about paper towels because it’s a more ostentatious demonstration of “wastefulness” than a lot of other things that I do – consuming electricity playing video games, or calling Ubers when I accidentally buy too many groceries to carry comfortably, or taking showers that are longer than strictly necessary? Would it actually be better for the environment to switch to using dish towels, or would it be like switching from plastic bags to paper bags, which Taiwan did but then had to reverse because it was responsible for a “mountain of paper waste”?

2. What I assume, what I know, and what I want to know

One Kirkland roll of paper towel has 160 sheets, and our three-person household goes through around two or three rolls per month, so let’s average that to 400 sheets.

A slightly less amount of dish towels are needed compared to paper towels, as one or two max is needed per incident, no matter how big a spill might be. So let’s say that we’ll use 350 dish towels over the course of a month.

According to that blog post, 6 sheets of “unpaper towels” can be made per dish towel. If we buy one 12-pack of dish towel, and make 72 sheets, we will need to do around 5 wash cycles a month, which seems unrealistic because all three of us are lazy. So let’s double the amount that we buy, and wash them 2.5 times a month, or roughly once every 2 weeks.

Realistically speaking, we’ll likely have to replace the dish towels once in a while, as they get stained and dingy and progressively less absorbent (especially if I forget to not use fabric softener). Over the course of the year they’ll get washed like 26 times, which sounds like a lot of times, so let’s just say that we replace them once a year for now.

So then, what I need to compare is:

- The impact of producing and disposing of (2.5*12) 30 rolls of paper towels

- The impact of producing and disposing of 24 of those cotton dish towels + the impact of washing/drying them 26 times.

For the sake of simplicity, I’ll be comparing their global warming potentials (GWP), in g CO2 eq. (basically, damage equivalent to grams of CO2 released into the environment), as it is a fairly comprehensive metric. The higher this number is, the worse it is for the environment.

3. The impact of paper towels

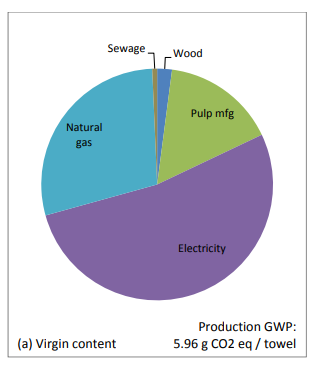

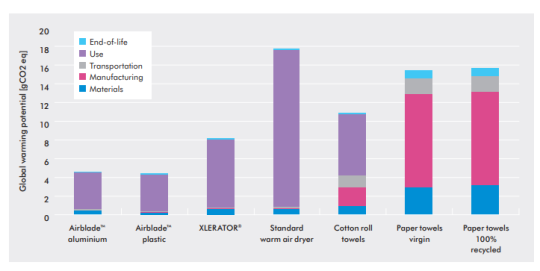

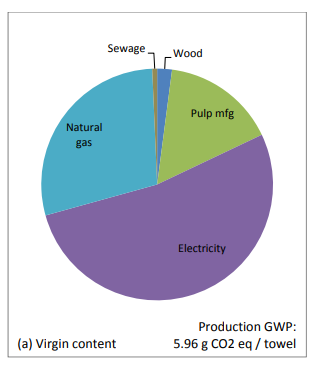

I found a report commissioned by Dyson Inc. and prepared by MIT, about the environmental effects of different ways of hand-drying at public restrooms over the life cycle of the product. The one product closest to our Costco Kirkland paper towels are likely the virgin paper towels. One towel has been specified to be 0.99g.

(fig.18)

(from the executive summary)

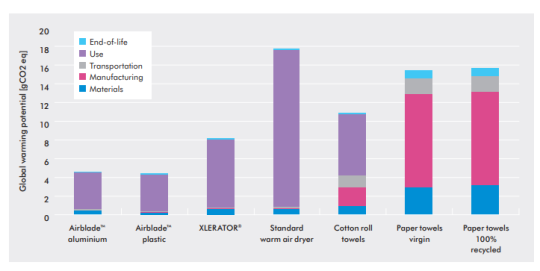

To clarify, there’s a difference between the GWP in fig.18 and the bar chart because the bar chart is calculating the lifespan GWP of two paper towels (they amount assumed necessary to dry a pair of hands), from production to packaging to transport to disposal.

These sheets are thinner than paper towels, but the materials and process is likely very similar, so I wouldn’t expect a large difference in the global warming equivalent per gram.

Using what we know from the charts here, we can see that 1 gram of paper towel has a GWP of (15.5g CO2 eq./1.98) approximately 7.8282 g CO2 eq.

One sheet of Kirkland paper towel is 2.12g, which means over the course of the month we go through 848g (400 sheets). That 848g has a GWP of approximately 6638.38 g CO2 eq. That works out to a GWP of 79 660.56 g CO2 eq., or 79.66 kg CO2 eq. per year.

4. The Impact of Cotton Towels

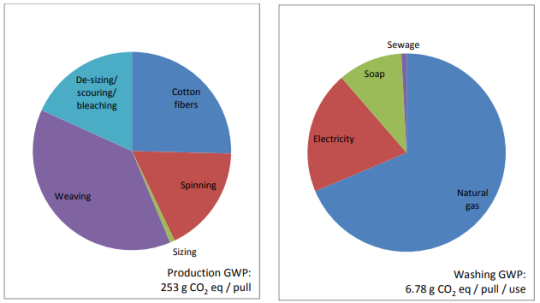

I am pleased to inform you that the aforementioned report also deals with cotton towels, so I basically had to do no work.

(fig 16, 17)

The report mentions that cotton towels can be laundered and reused an average of 103 times. This is 4 times longer than my expectation, but these towels are also used much more gently, and so can presumably be washed much more gently. That large amount of laundering is also why the bar graph in the previous section shows that cotton towels are less impactful than paper towels per use – the production GWP is distributed across 103 uses, making it almost negligible.

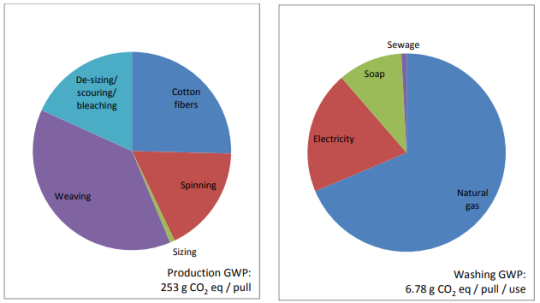

One standard cotton roll is 40m x 39cm-ish. I assume that because of the giant economies of scale in cotton production, the amount of energy needed to produce a size of cotton cloth doesn’t scale linearly. However, let’s just make sure that we’re at least on the same order of magnitude:

40m * 0.39m = 15.6m²

28in * 28in * 24 = 130.7ft² = 12.14m²

That’s pretty close, so let’s just use the original production GWP of 253g CO2 eq.

Cotton is easily recyclable so there’s a negligible end-of-life cost. I don’t think we need to worry about it too much.

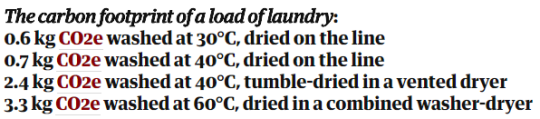

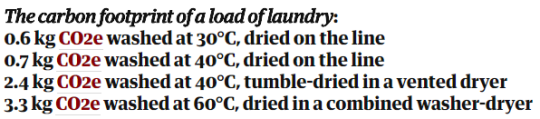

I’m not sure how relevant that washing GWP is since I sure don’t have an industrial bulk washer, so I’m going to use The Guardian’s stats for domestic laundry machines:

Oh, that… basically overwhelms any other impact that cotton towels can have over its lifespan. It does look like tumble drying adds like 1.7kg of CO2 eq. to the GWP per wash, so if we line-dry, even if we use hot water we’ll get an annual** GWP of 41.85 kg CO2 eq.**, pushihg us below the GWP of paper towels.

Realistically though, we’d be using that last option, at 3.3kg CO2 eq. per wash – hot water and bleach is probably necessary to keep those towels looking good, and we don’t have enough space to air dry 144 towels at once. So that works out to a GWP of 3.3kg CO2 eq * 26 = 85.8 kg CO2 eq. Adding on the production costs, we get an annual GWP of 86.05 kg CO2 eq. – higher than the GWP for paper towel use, but not by much.

5. I Do The Thing

So what’s the real moral here? Is it simply that cotton is better than paper, but only if you line dry? Is it that, actually, the real planet killers are tumble dryers? Or is it that anything environmental done on an individual basis is inconsequential? Recycling was already useless but became even more useless this year. Avoiding plastic bags does nothing. Using tissues and paper towels to your heart’s content will have absolutely no impact. And that makes sense – as this one Guardian article puts it, the people responsible for 2/3rds of all climate change? “They could all fit on a Greyhound bus or two.” And since they’re all profiting wildly from it, it makes sense that a narrative will be spun about how we individuals are all culpable.

We’re not. Look, I live in a very developed country, I buy a lot of things, and in terms of personal carbon footprint mine is probably in the largest 1% globally. According to this quiz, I emit around 12.4 tonnes of carbon annually.

Do you know how little that is? Cool Earth, the environmental charity that I have a recurring donation to, can save one tonne of CO2 equivalent for every USD $1.34. No, I did not misplace a decimal. Canadians, if you donate $20 to them, you’re home free for the year. I donate $10 per month, which means my carbon footprint is net negative. I can literally eat steak for every meal, run my laundry machine every day, and fly to LA every weekend, and it would still be net negative.

This paper/cotton towel thing is honestly not worth worrying about. What’s a few kilograms’ difference of CO2 equivalent in the context of 12.4 tonnes?

What I don’t mean by this is that I should check out of caring about the environment entirely. What I mean is that it’s important to realize the most effective way to actually bring about change, and then to laser focus on that. Political advocacy, as well as donations to effective environmental charities, can go exponentially (or maybe even hyperbolically!) further than trying to make your household “eco-friendly”.